By Peggy Eppig, Conservation Educator

Winter with all its blustery cold is a good time to hike among the sheltering trees. It’s a great time to experience the winter woods and enjoy how forests create protective habitat for even the most extreme winter weather. Within and on the edge of our forests, you can find a few trees that seem to excel in their roles as winter protectors. With distinctive bark, foliage, or growth habits, these make wonderful species for “meet-and-greets” with kids or grandkids and serve to teach identification and appreciation for critical winter refuge.

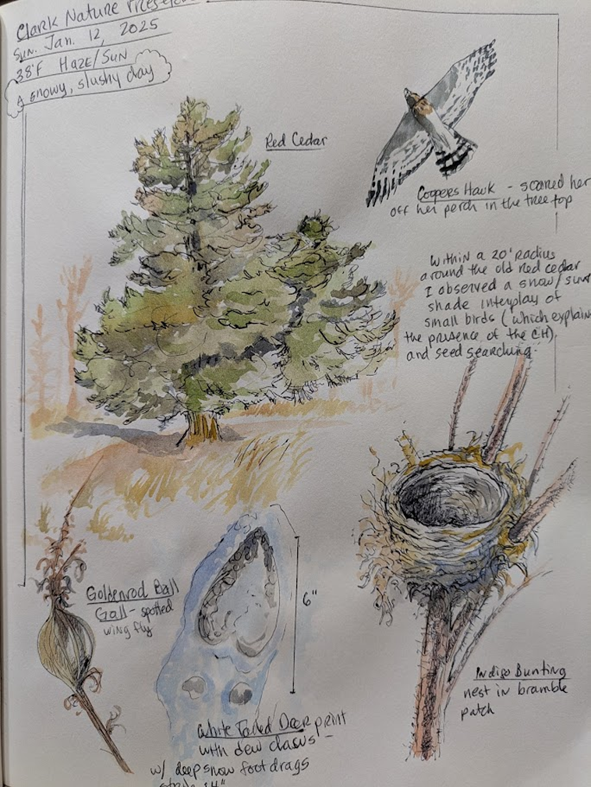

Eastern Redcedar

Find this tree at Clark Nature Preserve

Not actually a cedar but a juniper species, eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) is an iconic evergreen species found commonly in old fields and pastures. With wood that is rot-resistant and dense, its silver-grey trunks may stand for decades, long after a mature successional forest has overtaken pastureland and neglected fields. Hikers heading down the Ralph Goodno Loop Trail at Clark Nature Preserve towards House Rock will find dozens of old dead standing redcedar near the ruins of farm buildings and barns, indicating what was once open crop or grazing land. Visit the old “grandmother” redcedar at the top of the hill in the restoration meadow at Clark, and note how many birds and mammals are feeding within its dense canopy and foraging on the ground below, all feasting on the fleshy, cone-like blue berries.

Redcedar are dioecious, with male trees forming cones at their branch ends that open in spring to float pollen on the meadow breezes to the female’s yellow flowers which, when fertilized, will become those delicious, nutritious cone berries!

Eastern redcedar are excellent winter shelter trees. Flocks of cedar waxwings will roost in them through storms, sharing space with mixed flocks of dark-eyed juncos, chickadees, white-breasted nuthatches, goldfinches, and cardinals. White-tailed deer will bed down under its snow-laden limbs while snacking on its lower clumps of fragrant, scaly leaves. Look for signs of opossums and skunks digging up insects in the snow-free zone. At night, red foxes and coyotes will mark trunks and exposed roots to declare territory while screech owls watch from above. A sentinel redcedar is a magnet for winter wildlife no matter the cold and wind.

Hackberry

Find this tree at Wizard Ranch and Kellys Run nature preserves

Hedgerows or field edges that include a stand of hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) signal an important winter shelterbelt for animals and birds. Young hackberry trees growing in linear stands provide significant wind protection and are attractive places for wildlife to spend cold, windy winter days and nights.

Hackberry trunks have pronounced ridges of cork-like bark that act as a wind baffle to deflect wind. As hackberry trees mature, the corky bark may smooth out a bit but some high, defined ridges remain to form impressive slabs and scales large enough to serve as winter bat roosts and insect refugia for periods of winter diapause. In the windless coves of hackberry stands, a covey of bobwhite quails may be found hunkering down to wait out a blizzard or Arctic winds. Turkeys, fox sparrows, yellow-bellied sapsuckers, and grouse are very fond of foraging for hackberry seeds on the ground beneath their winter limbs or insects hiding in the deep crevices at the base of their distinctive trunks.

Hackberry is a great tree to have for butterflies. The question mark, American snout, and comma butterflies depend on its protection for overwintering eggs and early spring food resources for caterpillars. Hackberry emperor and mourning cloak butterflies are especially fond of this tree in forest settings and shelterbelts.

American Sycamore

Find this tree at Fox Hollow Nature Preserve

I don’t know of a better cavity provider than the American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) that grow along the many streambanks on Conservancy preserves. As young trees they have colorful, plated bark that shears off as the tree grows in girth. As they age and develop their distinctive bone-white major limb structure, a hallmark of their presence in our winter woods, their older limbs and trunk hollow out. Cavities are exposed where older limbs fall away, and if the trunk itself is damaged in a storm or fire, huge hollow openings will form that are big enough for large mammals to claim as dens.

On your next winter walk through the woods, take binoculars to see the cavities higher up. You may see which cavities are active with animals inside by looking for claw and beak wear on cavity rims. Grey foxes love hollow sycamore trunks for winter dens, as do black bears. In spring, larger cave-like hollows may house chimney swifts and tree swallows, but in winter, cavity holes higher up the trunk and at the end of snapped limbs are occupied with screech owls and barred owls that can often be seen sunning on bright winter days at the entrance to their tree hole homes.

Sycamores serve as cache sites for collectors of nuts, dried mushrooms, and berries. Explore the detritus that builds up around the base of a sycamore for what might be stored inside. Mice will fill smaller cavities with their fluffy nests while storing acorns in another small cavity nearby. Grey squirrels and raccoons often compete for prime cavity space, and when there’s a disagreement over who lays claim, the entire woods surrounding a contested tree will echo with their screeching chatter.

Black Cherry and American Beech

Find these trees at Otter Creek and Shiprock Woods nature preserves

In the winter woods, we can see how trees shelter each other. The pairing of the thick plated bark black cherry (Prunus serotina) with the thin bark American beech (Fagus grandifolia) can be found across slopes and exposed ridges. Often growing against each other as they mature, frost- and cold-sensitive seedlings germinate and grow in the protected root coves of the cherry, where sunlight is absorbed by the dark cherry bark and heat pockets form and where the ground is less likely to freeze. Unlike a nurse log that provides rotting wood and rich detritus for seedlings to grow into and from, a shelter tree provides protection against harsh winter wind and ice. Cherry trees offer beech saplings safe harbor against snow and slope that would otherwise challenge a sapling growing in such an environment.

Shelter trees may also provide some protection against browsers like white-tailed deer. For shade-tolerant beech, having a shelter tree to protect it through the leafless winter is a bonus for when spring comes and it is sheltered from the sun by the shade of its protector.

Even with a shelter tree to help it through harsh winters, you may still observe signs of cold weather damage on American beech, including frost cracking (see photo); seeping gnaw marks by squirrels and other rodents who are getting at the green, sweet living layer of sapwood beneath the thin bark; and browse marks by bark-eating deer that can strip a beech vertically from base to shoulder height. For these trees, it’s good to have at least a little shelter against the challenges of winter.