Environmental history is a relatively new field of study that emerged with the realization that the desire and need to better understand our current and potential future environmental issues was inextricably linked with our history. This vital field of study has illuminated not only our past, but where we are and where we’re going, and what we need to do to protect our planet and all of the creatures that inhabit it.

The Conservancy was very lucky this summer to welcome Peggy Eppig to our education team. She brings with her a wealth of knowledge and experience in environmental history – with a creative flair to boot! Recently, she answered a few questions for us on her own experiences and passion for the field of environmental history, and its relevance to us today.

A black vulture study created by Peggy

What inspires you most about learning and teaching environmental history?

I have two main interests that converge in the field of environmental history – hiking and forest history. I love the challenges hiking presents for both body and spirit and I love reading the forested landscape for signs – some obvious and some not – of past human relationships to the environment. Environmental history really is just a fancy way of describing how historians discover and interpret those relationships over time. It is very hands-on, very experiential. When I teach environmental history, my students are outdoors as much as they are indoors, maybe more! In addition, introducing students to resources like local historical societies, doing oral history, and investigating museum collections helps connect them to their own land communities and cultural histories.

Can you share one of your favorite interesting facts or stories about our area?

The colonial iron-making industry in this area profoundly changed our environment in South-Central Pennsylvania. When we’re hiking a favorite trail there are visible clues that help describe what the land looked like and how it functioned over three hundred years ago. There are furnace ruins to investigate, charcoal hearths, charcoal wagon roads, quarry pits and mines – all visible from the trail and once you know what to look and how to document your finds, the hiker will become aware of less obvious clues like why certain plants communities are found in certain areas or how past water management structures have become important wetlands for wildlife. The forest we have today is partly a result of the iron industry’s forest clearances in the 1700 and 1800s, so tree types and ages are clues to the scale and technologies of timber harvesting hundreds of years ago. Almost all our preserves have evidence of charcoal making which required harvesting up to a thousand acres of forest to fuel an iron furnace every year! How these lands recovered to be the beautiful preserves they are today make for great stories of resilience and stewardship.

Peggy on one of her many adventures!

Can you tell us about some of the historical adventures you’ve taken?

One of my favorite adventures was walking the Camino de Santiago from France across Spain, not for any religious reason (as many people do) but to observe the tremendous changes in the landscape that include rewilding efforts by conservationists as they help address the opportunities for wildlife that come with rural depopulation. Every day on that six-week hike I observed plants, birds, mammals, reptiles, and semi-wilderness that haven’t been observed since before the Middle Ages. The rewilding movement is strong in Europe, and I saw the Camino path as an opportunity to walk a transect across a country, to witness an amazing recovery of biodiversity and support the conservationists who are doing this work.

One of my favorite experiences on my Camino walk was walking with two conservation pilgrims (like me) who were graduate students in Madrid. We walked for a few days together when they received word via their program supervisor that a den of Iberian wolf puppies had been observed in their study area! The first Iberian wolves born in the wild in Spain in 500 years! That night we celebrated with the wildlife photographer who had been among the first to see the pups emerge from their den in Galicia just days before. This was a huge success for conservation in Spain – and I was there!

Why is environmental history important and relevant to us today?

I am passionate about learning from the past so that we can manage for healthy, biodiverse landscapes in the present and for future generations. The professional field of environmental history is full of researchers, authors, and scientists who feel the same way I do. Environmental histories of past pandemics, for instance, helped us these past few years understand how germs travel through the environment. Environmental histories of great droughts, exploitative industries, or industrial agriculture help us think about better ways to manage soil, water, and waste.

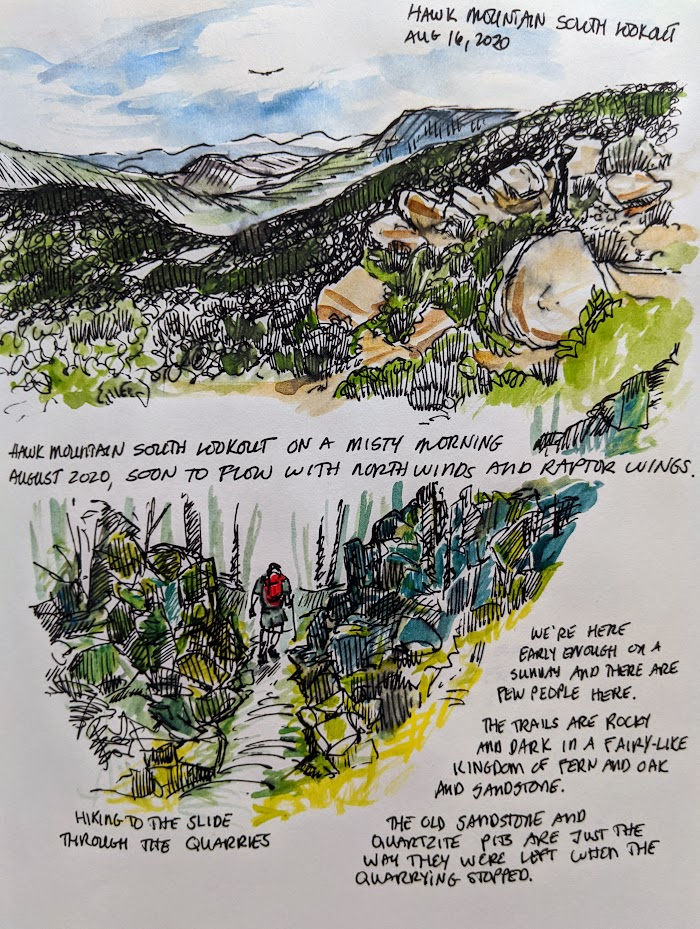

A page from Peggy’s nature journal

What are some important things to consider when exploring nature from a historical lens?

Elements of the history of nature and people are embedded in the soil, rocks, forests, and waters of our landscapes. We can understand those elements only in the context of the environment. To remove one element – a deer antler, a shard of pottery, a turtle shell, or a projectile point – is to starve the land of an important element of that story and make it unavailable to future “readers.” We can’t read the whole story with words, phrases, and sentences missing!

When I’m out hiking, I carry a few things that maybe not every hiker carries. I always have my sketch journal, my phone camera (sometimes a bigger fancier camera, too), a small trowel, a photo-scale measure, and always binoculars. Did you know that binoculars can be used to see up close and far away? These are things that help me read the clues a little better. I scrape a little soil to find black bits of burnt wood under the forest duff to confirm a 300-year-old charcoal hearth. I use my photo-scale to take a picture of an old wall or rusty piece of iron tool. I sketch the lay of the land that include canals, ditches, and foundations. I never remove anything from the land. It would be like ripping a page out of a very good book. I love to follow up my hiking investigations with a visit to one of our excellent local museums with my sketchbook to compare what is in collection to what I discovered on the land. Sometimes my sketches and photos provide valuable information to historians. That makes my day!

Can you tell us about what first sparked your interest in the intersection between the study of the environment and history?

I have ancestors who lived and farmed in what is now Shenandoah National Park. Our family’s “history hikes” go back a long way and when I was in my teens, these hikes became monumental expeditions of old and young folks hiking together to find a cabin site, remains of a barn, or an old road. Honestly, I was just as happy to find a salamander or see a bear, but I learned so much from my great uncles and aunts about how they loved their land and how they lived from it. Now I love to share these hikes with my own grandchildren. We still take these great hikes in the Appalachian Mountains with the same joy and reverence for our ancestors and their relationship to the land!