By Keith Williams, Vice President of Engagement & Education

I hiked south on the Mason-Dixon Trail into the heart of the forest that is proposed to be submerged. The best way to experience the natural import of the area around Cuffs Run, where the stream enters the Susquehanna River, is on foot. This area is about as rugged and removed as it gets around here anymore. Most of these wild places have been exterminated from this part of Pennsylvania and the northeast. They have been eradicated because we don’t view these places as sacred, we view them as commodities – as things that can be ordered and traded, bought and sold. They are reduced from ethereal treasures to dollar signs.

The concept that threatens to destroy this landscape is simple and lucrative: pump water up from the Susquehanna into a created lake when electricity is cheap, then flow it back downhill through turbines when electricity can be sold for more. There is no net gain in electricity.

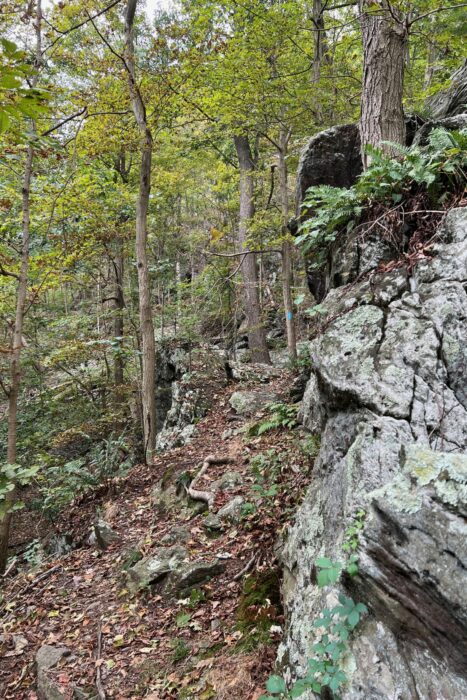

Part of the 200-mile-long Mason-Dixon Trail threads through this landscape, twisting among rocky crags between cleaved hunks of schist, ancient mudstone exposed to heat and pressure so that it forms ropy bands that shimmer with mica. Chunks of quartz are perched in the schist, fissures that filled with silica precipitated out of the ancient sea and mineralized over time to form quartz.

Enormous tree trunks lay horizontal on the ground. I think they’re old tulip poplars, resting on the earth for maybe 100 years based on the amount of rot, after standing for 200 based on their girth. Their enormity gives a glimpse of what was here. There are still a few large individuals standing, old souls who may be three centuries old. But they won’t make it another 10 years if this pumped storage project goes in.

The trail is narrow, rocky, and steep until it enters a plateau dominated by oak. This is probably what the landscape looked like before Europeans settled here, when indigenous people stewarded this land in tune and sync with natural cycles, when plants and animals were viewed as beings rather than things, when nature reigned.

This spot is the edge of the magic. All of the forest until now is special, but this is the beginning of something especially significant – a time portal offering a view into our collective ecological past, a common ancestry, and the heart of the proposed Cuffs Run pumped storage project, which would bury this place forever with over a mile of concrete and hundreds of acres of mud and water.

The trail starts a gentle descent from the plateau, and the soft duff becomes hard and rocky. The timelessness of the place depends on these rocks that start to emerge from beneath the spongy forest soil until the landscape becomes a boulder field. Its ruggedness and remoteness that have kept it safe until now also depends on its rocky nature. This area has historically been inaccessible to motorized vehicles like logging trucks and dozers thanks to the bedrock outcropping here, so the ancients prevail. Here are the ancient rocks and the ancient beings they support and protect.

Aquamarine lichens glow against the grey schist and white quartz veins. These are some of the oldest living beings on the planet. To put it simply they are beautiful, and their longevity makes them even more special. This raggedy edged lichen plastered to a quartz boulder could be 5,000 years old. They are a cooperation, a symbiosis of a fungi and algae, adding more power to the idea of survival of the cooperative versus survival of the fittest. Darwin be damned, we need to cooperate with this landscape, not compete with it, not view it as profit margin.

The trail starts to steepen to match the terrain, and the rocks start to dominate. Oaks and cedars somehow grow between the slabs of schist, creating a small patch of oak cedar savanna. Given the age of cedars on the Niagara escarpment (1,300 years old), I wonder the age of the cedars in the Cuffs Run oak cedar rock savannah. Again, my marvel is tempered by the reality of possible destruction fueled simply by greed. Who are we to eliminate 1,000-year-old beings? I continue down a steep hill through an oak juniper savanna, past ancient white, red, and chestnut oak and cedar who grow from the smallest of cracks in the geology and pour their roots over the rocks as if they were molten. Then the steep hill turns to cliff face and the trail amazingly weaves its way downhill on narrow rock shelves formed by the cleaved schist bedrock.

It’s a challenge to navigate this landscape. Humans almost don’t belong here. And that encapsulates the need for Cuffs Run to exist. There are economic, social, and ecological reasons, but ultimately, Cuffs Run needs to exist simply because it is. Wild places like this need to continue existing somewhere in the world.

Economically, the pumped storage project proposed for Cuffs Run will line the pockets of a few to the detriment of many. Forty-nine properties will be taken over. Ancient ecology will be destroyed. Critical ecosystem services will be lost, like the carbon sequestration abilities of hundreds of acres of forest. And most importantly to me, we will lose the knowledge that this wild space exists.

But for now, in the present, I am hiking down a cliff that drops to the creek below – Cuffs Run. I pass by rock shelves that support thin soils where rock polypody ferns grow. Adapted to live through desiccation and inundation, hot and dry, wet and frozen, they have navigated this difficulty for tens of thousands of years. And now a new threat emerges that isn’t survivable.

I reach the bottom of the steep valley. The stream, which has cut down through the schist over eons, exemplifies the observation Lucretius made more than 2,000 years ago that water does, in fact, wear away stone. It’s a good reminder for the masses poised to fight this project. The stream cascades over short waterfalls on its way to the Susquehanna, wearing away the stone that forms the chutes.

I start the steep ascent up the other side of the valley, through more boulder fields. Ancient sweet birch grow up from between the slabs, and their giant roots look like they were poured over rocks. I do not know how trees can survive here, but they do – a testament to tenacity. A huge tree, probably more than 200 years old, grows from just the tiniest of fissures. Let these be inspiration to us all as we take on the fight to protect this unique landscape.

I wonder if there were ever rattlesnakes here. There should have been, and maybe there still are. The range of eastern timber rattlers is shrinking – more reduction of the wild. But with all the rocky crags here, maybe they still exist. It would add to the wildness. Add to the fact that I’m not in control here. There is a force that is greater than me running the show. Wild places are dictated by the rhythms of nature and time. They are places where we are not in control. Wild places remind me that I’m just a tiny piece of this much larger whole, which puts things into perspective for me. It’s reassuring to know that there is this power greater than myself.

Wild places remind me of where I am, and point me in the direction of where I’m supposed to be. They show me that in the chaos, there is order. Homo sapiens started on the savanna 300,000 years ago. Nature and wildness are coded into our DNA. It’s only been 300 years since we started to consider ourselves superior to nature and began the separation and destruction. As we separate from nature we lose connection, lose the emotional relationship with our world, though the physical dependency remains. We cannot survive emotionally, spiritually, or physically without nature. We all need wildness.

What defines a place is the collection of the individual pieces – the trees, the shrubs, the wildflowers, the amphibians, the reptiles, the insects, the mammals. All these pieces are connected to each other, all placed onto the bones of the landscape. The collection of beings gives the place its spirit. If some parts are submerged by a reservoir or razed to build buildings or transport structures, the whole collection thins, and this place would lose its character, becoming homogenized like so much of the rest of this part of the world. Industrialized. Tamed. Bland.

How do you capture the spirit of a place? I don’t think you can. But you can drown it.

It’s a hard ascent up the south canyon wall, but worth every bit of the effort. This is what this landscape has been for the last 10,000 years. This is the time portal, giving glimpses into our collective ecological pasts and a vision of the hopeful future. These places – boulder fields and outcrops – are biodiversity hotspots and biological arcs that will carry biodiversity into the future in the face of climate change. For now, organisms can find the right conditions here when they don’t exist anywhere else.

I step up into a slot in the bedrock cliff and hike through with my shoulders touching both rock walls. On the other side is a stunted but mature oak forest with a low bush blueberry and huckleberry shrub layer. This is another unique system, not common around here anymore. The wind whips up off the river and makes me feel alive.

I stand on the edge of the outcrop beneath pines and oaks and look out over the river and the Cuffs Run gorge below. I picture it flooded, destroyed.

Two young eagles try to soar overhead. They are clumsy as they hone their new aerial skill, and they whimper to each other. There’s hope in these birds, since they were almost driven from the face of the Earth by our hand. They are symbols that we can reverse damage, that we can change course to do the right thing.

And here is hope in Cuffs Run. We can defeat the proposed pumped storage facility. The community is already rallying around this special place.

All photos in this blog were taken by Keith Williams.