by Keith Williams, Naturalist and Community Engagement Coordinator, Lancaster Conservancy

The rippling surface of a vernal pool. Photo: Keith Williams

I was walking along a path at Climbers Run Nature Center, when suddenly, it seemed as though the woods erupted with sound – a chorus of hoarse squeaks. The weak sun had finally burned through the mid-March overcast, raising the temperature just a few degrees – and that’s when the calling started. I followed the sound which brought me to a large puddle. The surface was dappled with activity. I took another step closer and the squeaking stopped. The woods became as quiet as they were moments before, with just the wind hissing through the boxelder branches above. The surface of the puddle became glass smooth.

I sat on a log and waited motionless. A few moments passed before the first deep nasal squeak came again from the pool, then a second, and then the rest of the chorus joined in. The sound again filled the forest and the surface of the pool danced with ripples.

All that noise and commotion was the start of the next generation of wood frogs, gathered in a vernal pool. They are some of the first emerging amphibians in spring, and while their calls serve to attract a mate, I like to think that their calls serve another purpose as well – celebrating these small creatures’ return to life. They just survived freezing and cardiac arrest. Over winter wood frogs have the ability to freeze through. They stop breathing and their hearts stop beating. When temperatures warm, they thaw out and their hearts start to beat again. I think it is very possible that their calls are part mate attraction and part celebration of being alive. These miraculous creatures are part of a procession of life that depends on temporary habitats for the survival of their species.

Clusters of eggs in a vernal pool. Photo: Keith Williams

Vernal pools are that temporary habitat. Vernal pools are seasonal depressional wetlands covered by shallow water for variable periods from winter to spring, and are completely dry in summer and fall. They can come about a number of ways. In some places, a clay lens beneath the surface lets shallow depressions collect water in winter and spring. Sometimes their formation is due to physical disturbance, like the divot left in the forest floor from when a tree uproots. This particular one, where the wood frogs gather on Climbers Run Nature Preserve, is part of an old stream channel, a remnant from before the creek made a short cut across a bend.

Amphibians spend part of their lives in water as gilled forms, usually when they are juveniles, and many species become more terrestrial as adults. Vernal pool use for breeding is a strategy that depends on a temporary aquatic habitat. If you are an amphibian parent, you want your vernal pool to be wet long enough for your babies to grow lungs, sprout legs, and walk or hop away, but not long enough for populations of predators who might eat your young to establish. In late winter and early spring, on days and especially nights that feel too cold for ectothermic (or cold blooded) organisms to be out and about, we find frogs like these wood frogs, spring peepers, and salamanders, wandering the woods, heading to their vernal pool.

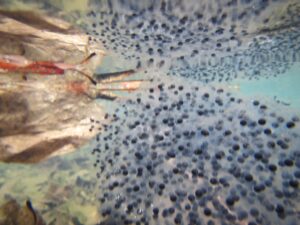

Clusters of eggs in a vernal pool. Photo: Keith Williams

Two days after my first discovery of the vernal pool, temperatures dropped, and the pool was silent. I visited it again – creeping in slowly. Large gelatinous masses of salamander eggs were wrapped around twigs like large jelly lollipops, while clusters of frog eggs floated freely in the pool. Each embryo was visible as a large dark comma in the center of each egg. This was the next generation of wood frog and salamander, probably one of the mole salamander species which include the spotted, marbled and tiger salamander. Most mole salamander species are considered stable, however some populations are declining. While vernal pools are wetlands, they are usually too small to qualify for protection under the Clean Water Act, and habitat loss, both wetland and forest, is a driving reason for the declines we see in some mole salamander species populations.

I looked hard into the water and strained to see faint ghostly waifs. Fairy shrimp employ a different strategy to capitalize on temporary wetland habits, and I hoped to see the brief adult stage of these federally protected invertebrates. Fairy shrimp are translucent one-inch long crustaceans, cousin of crabs and lobsters, who swim upside down and eat algae and plankton growing in the vernal pool. These fairy shrimp are listed as federally threatened due to habitat loss and alteration, which means we have acknowledged populations are in decline to the point they are at risk of forever ceasing to exist.

A vernal pool at Climbers Run Nature Center. Photo: Lydia Martin

I again returned to the pool a few days later and sat on a nearby log. The skunk cabbages were starting to unfurl their large luxuriant green leaves, though a few were still just dappled maroon hoods peeking through the soft mud. The wood frogs were back and calling with all their might, all their energy focused on finding a mate. Life in a vernal pool is fleeting. The clock is ticking.

I got up and slowly moved away so as to not disturb the wood frogs and give them space to celebrate and mate. They were, after all, just frozen and in cardiac arrest a few weeks ago. There is much to catch up on.